Here are the three main points to remember from COP27's Sharm el-Sheikh Agreement.

COP27 was a mixed bag. Frustratingly, little progress was made on the reduction of fossil fuels. But there was much focus on climate justice and adaptation with the creation of a fund dedicated to the Loss and Damage Mechanism.

Here are my three takeaways:

-

Creation of a loss and damage fund

-

Reassertion of our global 1.5 C climate target

-

Greater focus on adaptation and increase in adaptation funding

1. A historic breakthrough on loss and damage but the implementation modalities remain unclear

❓Loss & Damage, what is it?

Loss and damages are the reparations claimed from wealthy countries (main culprits of global warming) by poor countries (main victims of climate disruption) for the damage already suffered. It's the money needed to rescue and rebuild the physical and social infrastructure of countries devastated by extreme weather for nearly three decades.

For the first time, they were officially put on the COP agenda and wealthy countries, led by the European Union, made proposals on the subject.

“We've been fighting for 30 years and today in Sharm el-Sheikh, this epic journey has produced its first positive result," said Sherry Rehman, Pakistan's Climate Change Minister and current chair of the G77+China negotiating group. "Establishing a fund isn't a matter of charity. It's clearly a down payment on the longer term investment in our common future and an investment in climate justice."

👉 The final decision is the creation of a Loss and Damage Response Fund. It should benefit all developing countries and will be directed first to the most vulnerable countries.

The European Union is lobbying to include among the donors the new major contributors of emissions: China but also Saudi Arabia and more globally the Gulf monarchies whose fortune comes from oil and gas.

The Ad Hoc Committee for Adoption will therefore present its proposals at the next COP28, which will take place in… the United Arab Emirates!

🤨 But, the implementation methods remain unclear: Who pays, who gets the money, how much, and how?

The way in which the fund will be implemented will be worked out by a special committee for adoption at the next COP. It'll be responsible for identifying sources of funding and defining the financial contribution of developed countries and major emitters to the mitigation and adaptation fund.

This is a first step towards climate justice but it is still not enough. So far the target of developed countries in 2015 by the Paris Agreement to jointly mobilize $100B still hasn’t been met.

2. Reassertion of our global 1.5 C climate target but the commitments remain too weak

🌡️ The most ambitious objective of the Paris Agreement, the limitation of global warming to +1.5°C, is increasingly undermined as the thermometer rises.

"In the scenarios we've assessed, limiting warming to 1.5°C requires greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest," warned scientists from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in April 2022.

In the end, the emblematic figure is included in the final COP27 declaration, but no new means are mentioned to reinforce the credibility of this commitment. Countries that aren't on track with this trajectory are only weakly invited to update their greenhouse gas reduction targets by the end of 2023.

At present, the policies being pursued are leading us straight towards a warming of +2.8°C. "We need to drastically reduce emissions now. And this is a question that this COP has not answered," said Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General.

🛢️ No progress on fossil fuels, where coal, oil, and gas are still the crux of the climate problem.

Fossil fuels, which account for 80% of the world's energy consumption, are our main source of greenhouse gas emissions, the driving force behind human-induced global warming.

Last year in Glasgow, a commitment to phase down the use of coal was agreed. It was the first time a resolution on fossil fuels had been included in the final text. In Sharm el-Sheikh, India pushed for oil and gas, still widely used in developed countries, to be mentioned along with coal, an energy more prevalent in developing countries. This initiative fell through. The COP27 text repeats word for word the formula chosen at the Scottish COP26.

3. A greater focus on adaptation, but adaptation finance is well below our current and future needs

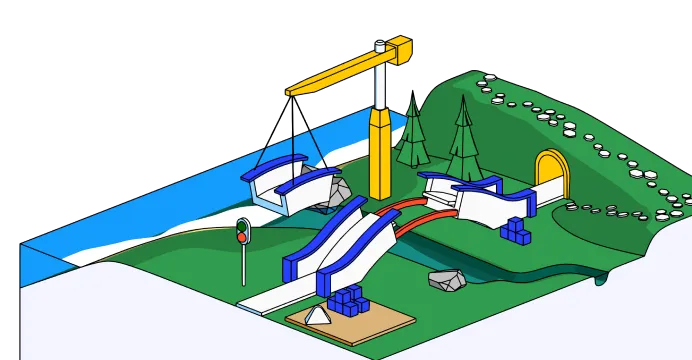

🚧 COP27 saw significant progress on adaptation, with governments agreeing on the way to move forward on the Global Goal on Adaptation, which will conclude at COP28 and inform the first Global Stocktake.

Adaptation: Building flood defenses, preserving wetlands, restoring mangrove swamps and regrowing forests – these measures, and more, can help countries to become more resilient to the impacts of climate breakdown. But poor countries often struggle to gain funding for these efforts. Of the $100B a year rich countries promised they would receive from 2020, only about $20B goes to adaptation.

New pledges, totaling more than $230M, were made to support the Adaptation Fund at COP27. These pledges will help many more vulnerable communities adapt to climate change through concrete adaptation solutions. COP27 President Sameh Shoukry announced the Sharm el-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda, enhancing resilience for people living in the most climate-vulnerable communities by 2030.

The UN Climate Change’s Standing Committee on Finance was requested to prepare a report on doubling adaptation finance for consideration at COP28 this year.

To achieve net-zero emissions, environmentally-vulnerable countries must invest trillions of dollars in capacity-building and green infrastructure. Climate economist Nicholas Stern has calculated the developing world will need $2.4T a year from 2030. But this is only about 5% more than the investment they would require anyway, much of which would go into high-carbon infrastructure. The World Bank could provide about half of those funds, he estimates.

A reform of the World Bank is needed: A growing number of developed and developing countries are calling for urgent changes to the World Bank and other publicly funded finance institutions, which they say have failed to provide the funding needed to help poor countries cut their greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the impacts of the climate crisis. Reform of the kind widely discussed at COP27 could involve a recapitalization of the development banks to allow them to provide far more assistance to the developing world.

Conclusion

💰 The COP27 was the COP of finance.

The cover decision, known as the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, highlights that a global transformation to a low-carbon economy is expected to require investments of at least $4-6T a year. Delivering such funding will require a swift and comprehensive transformation of the financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors, and other financial actors.

👉 Lots of work still to be done and time is growing short!